Note: This blog post may be outdated,

We discussed briefly the role of the Security Council in maintaining international peace, security and stability. Article 24 of the UN Charter says that as an organ of the United Nations, it is the Security Council that has the primary responsibility of maintaining international peace, security and stability. The Security Council can take measures that are binding on member States. Article 25 of the UN Charter says:

“The Members of the United Nations agree to accept and carry out the decisions of the Security Council in accordance with the present Charter.”

The General Assembly (GA) cannot take measures that are binding on States. The GA, in theory, cannot make recommendations on a dispute or situation when the Security Council is discussing it (Article 12 of the Charter). Article 10 says:

“The General Assembly may discuss any questions or any matters within the scope of the present Charter or relating to the powers and functions of any organs provided for in the present Charter, and, except as provided in Article 12, may make recommendations to the Members of the United Nations or to the Security Council or to both on any such questions or matters.”

In the Palestinian Wall Case, the ICJ held that the Security Council’s authority to maintain international peace and security was ‘primary’ but not ‘exclusive’✐ See A. 11 and 14 of the Charter. The GA, under the Uniting for Peace Resolution, can discuss and make recommendations on matters even when the Security Council is discussing them. Under this Resolution, the GA (1) referred the Palestinian Wall Case to the ICJ for an Advisory Opinion; and (2) sent a Peacekeeping force to Egypt after the Suez canal crisis in 1956 (even though the SC was simultaniously discussing these matters).

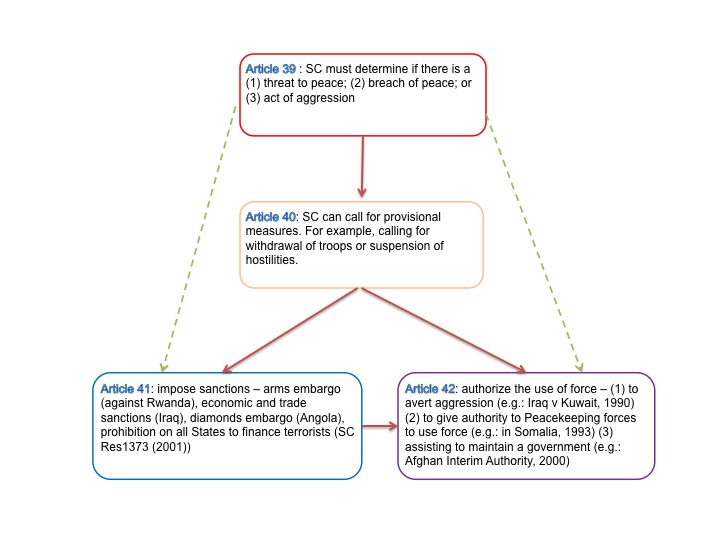

Figure 1: Options available to the UN Security Council in the event one State uses force against another State.

Under Article 53 of the Charter the Security Council can also authorize regional organizations such as NATO, OAS, OAU to take enforcement measures. For example, in 1995, the Security Council authorized NATO to take ‘all necessary measures’ to oversee the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Suggested reading:

Special Research Report No. 1: Security Council Action Under Chapter VII: Myths and Realities. The following is an extract of the report.

Summary

This report addresses eight issues:

-

Does the Council have the power to impose binding obligations without using Chapter VII?

-

What makes a Council decision binding?

-

Does the form of a Council decision matter—is an explicit mention of Chapter VII necessary?

-

Who can be bound by a Council decision?

-

Is a reference to Chapter VII necessary to authorise member states to use force?

-

Is a reference to Chapter VII necessary to authorise a robust mandate for a UN operation involving the use of military force?

-

Is it the Council resolution or the rules of engagement (ROE) and concept of operations that determine whether a UN operation will be able to use force?

-

Is a reference to Chapter VII necessary to impose sanctions?

The analysis in this report suggests the following conclusions:

-

The Council has general powers under articles 24 and 25 to adopt binding decisions and such decisions do not need to be always taken under Chapter VII.

-

Even when the Council does use its Chapter VII powers, it is not essential to have an explicit reference to Chapter VII or a particular article thereof.

-

Resolutions adopted under Chapter VII may also (and usually do) include provisions which are non-binding.

-

Interpretation of Council resolutions is a complex art. In order to ascertain the Council’s intent and the powers it may be using in a particular resolution, it is necessary to analyse the overall context, the precise terms used in the resolution and sometimes the discussions in the Council—both at the time of adoption and subsequently.

Although the express mention of Chapter VII is not essential, the Council seems in recent times to recognise increasingly the significant importance of clarity. The clearer the language adopted, the better the prospects for effectiveness and credibility of Council decisions. This may not be possible on every occasion, but it seems that on balance the Council is conscious of the need to avoid ambiguity. Other conclusions include:

-

Although the Charter does not expressly prescribe a particular form for adopting binding decisions, Council practice suggests that resolutions are the primary vehicle for binding decisions. Presidential and press statements are not used as vehicles for such decisions.

-

Council decisions bind member states and the United Nations itself—but there is uncertainty regarding non-member states and regional organisations. Sometimes it addresses individuals and non-state actors. Often, it appears to try to bind such parties. It remains to be seen how this practice will be viewed over time.

Our research and analysis also suggests that:

-

Chapter VII powers must be used for the establishment of Council-mandated sanctions regimes—although an explicit reference to the chapter or article 41 is not essential.

-

Similarly, use of Chapter VII powers is required to authorise member-states or a UN peacekeeping operation to use force—but again an explicit reference to the chapter is not essential.

-

However, the problems generated by uncertain consent, concern about legal ambiguity and deployment in increasingly hostile operational environments increasingly led the Council to begin to approve UN operations and to authorise the use of force with explicit reference to Chapter VII.

-

The practical conduct of UN peacekeeping operations—and whether force is actually used or not—is typically more strongly influenced by other factors such as the concept of operations and ROE rather than the language of the mandate itself.

© Ruwanthika Gunaratne and Public International Law at https://ruwanthikagunaratne.wordpress.com, 2008 – 2020. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Ruwanthika Gunaratne and Public International Law with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.